The Mobster Who Brought Down the Mob

MEN’S JOURNAL

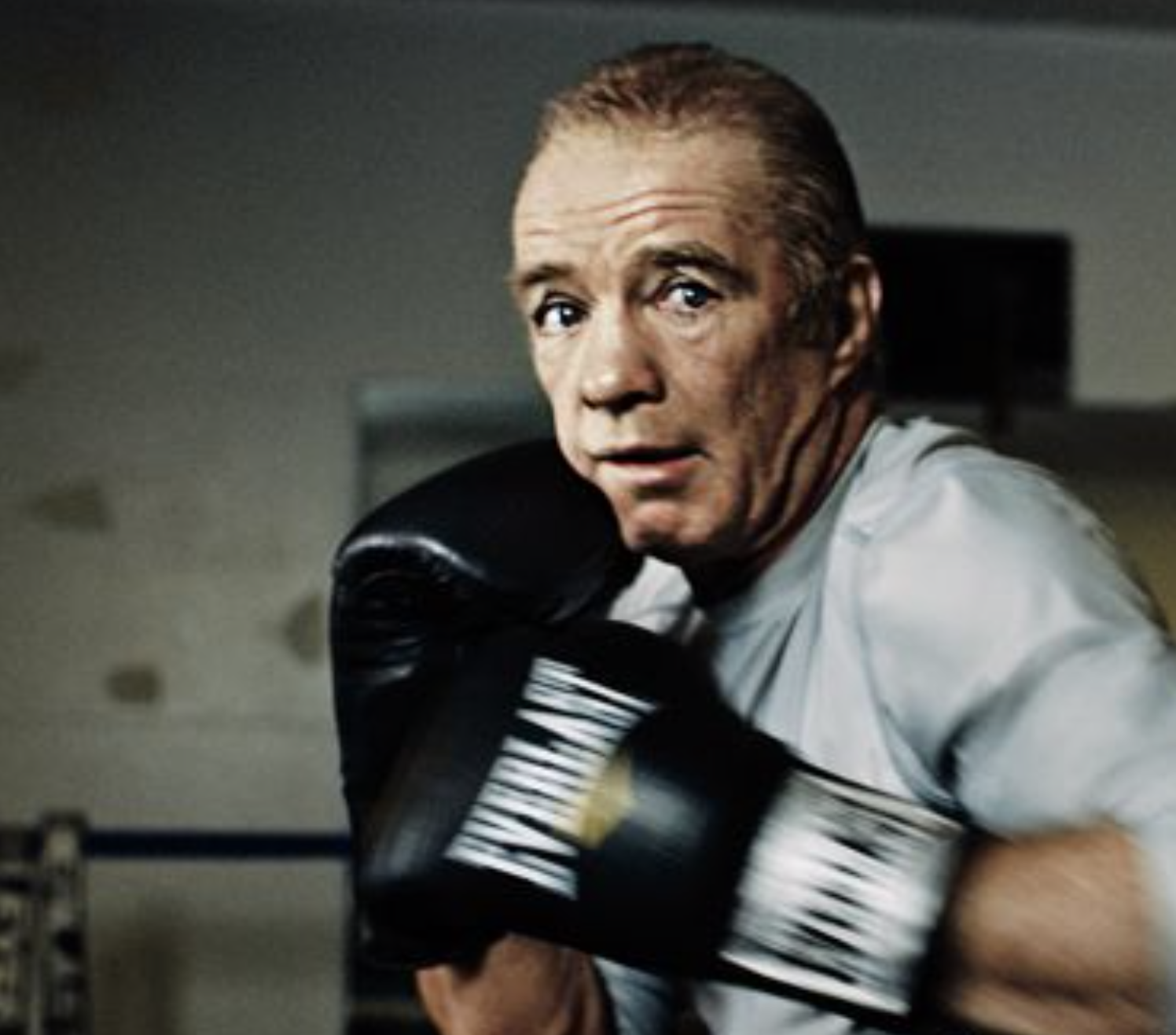

He’d been the perfect soldier. Tough, loyal, reliable. Even as a kid, Tommy McLaughlin had done whatever was asked of him – no complaints, no surprises. McLaughlin had proved he could keep his mouth shut. He was just 23 when he started serving 14 years on a drug charge he could have flipped on and gotten off easy. Half his life. He served every day of it, too. The hard way. Gang fights, turf wars, protection. Not easy at 5-foot-7. But he never mellowed, never backed down. Now, finally, it was his time.

At 38, Tommy McLaughlin was ready to collect on whatever he was owed for 14 years. He’d gotten married, and he and his wife were living with his sister, Joanne, and her husband, a convicted mob extortionist who had done time with McLaughlin in prison. All together in a Greek-columned four-bedroom, in the Prince’s Bay part of Staten Island, just a short walk from the beach. All in all, things could be worse. While he was away, a lot of the guys he’d come up with had risen in the ranks, replacing the older crew whose cars they’d washed as kids. His first cousin, Tommy Gioeli, was now the Colombo acting boss. The family was not what it once was: While he was in prison, omertà, their code of ironclad deniability, had basically gone to shit. But business was still good and they wouldn’t forget a guy like Tommy.

If it were only that easy.

They stepped right into his path on a street in Brooklyn. Two feds on foot with two more in a support car nearby. They laid it all out for him: he’d been the driver on a revenge killing back in ’91. He was fresh out of prison and they already wanted to send him back – and on a 20-year-old charge. Somebody must have given him up. A week or so later, the feds took him downtown, to the 22nd floor of the Federal Building in Lower Manhattan for a meeting. McLaughlin was disdainful, defiant, as agent Scott Curtis presented him with his options: Go back to prison for the rest of your life or come work for Team America.

On a cold January morning almost two years later, as many as 800 law-enforcement agents simultaneously apprehended more than 120 mid- and high-ranking members of the five crime syndicates that have dominated organized crime in New York for a century. Hardest hit by the raid was the Colombo family, considered to be one of the mob’s bloodiest outfits. “In a single day,” says FBI Special Agent Seamus McElearney, “we dismantled the entire Colombo hierarchy – the boss, underboss, consigliere, five captains, and seven soldiers.” Forty-eight of the arrests would be attributed to evidence collected by Tommy McLaughlin, the tough half-Irish kid who’d once been one of the family’s most loyal soldiers.

The Dyker Heights section of Brooklyn is the kind of place where a promising thug can make a name for himself. Just across the Verrazano Bridge from Staten Island, it is a choice slice of the Italian-American dream, Colombo style. The family has been dug in here since the ’40s, and entry-level work is still in abundance: construction, trucking, drugs, no-show union jobs, gun sales. Tommy McLaughlin was born and raised here, but by the time he hit puberty, he was left in the care of Joanne, who moved McLaughlin and his little brother to an apartment in Staten Island, essentially exiling him to “mob Siberia.”

But his life – and his living – remained in Brooklyn. He was small for a tough guy, but jacked. As Detective Joe Ierardi, who followed McLaughlin’s criminal ascent, puts it: “He wasn’t afraid of mixing it up. And that impressed all the wrong people.” Ellen Corcella, a former federal prosecutor who went after the Dyker Heights crew in the 1990s, is familiar with the indoctrination ritual. “These mob guys recruit kids who are 14 into their crews,” she says. “Literally, they get the chance to wash the big mobster’s car and hang out with him. Then, next thing you know, you’re invited to see him murder someone. Then you’re told to take care of someone.”

McLaughlin had his choice of willing mentors. Joanne was dating Bonanno-family hit man Tommy “Karate” Pitera, also known as “the Butcher” for a dozen vicious killings in the 1980s. Tommy Gioeli was running a Colombo crew of his own. But McLaughlin, who started off selling weed on the streets and worked his way up to command a major supply, found a role model in Greg Scarpa, a top captain for imprisoned family boss Carmine Persico and one of the most volatile guys around. He was so violent that when three civil rights workers went missing in Mississippi in 1964, J. Edgar Hoover sent him to investigate their disappearance. While there, Scarpa kidnapped a Klansman, beat him bloody, and stuck a gun barrel down his throat until he revealed the location of the victims. His nickname was “the Grim Reaper,” or alternatively, “the Mad Hatter,” and he took an immediate liking to McLaughlin.

“Scarpa really liked Tommy because he was a lot like Scarpa,” says Leon Rodriguez, a former Brooklyn prosecutor who investigated McLaughlin. “He was cold-blooded, tough, and willing to do whatever. And he wasn’t a complainer. One thing you learn about these guys is that they’re all a bunch of whiners.” McLaughlin was among the youngest of the crew hanging around Scarpa’s Dyker Heights home, a sanctum of Colombo activity.

But business wasn’t the only draw for McLaughlin at the Scarpa residence; there was also Scarpa’s teenage daughter, “Little” Linda Schiro. (Though she is Scarpa’s daughter, she uses her mother’s surname because Scarpa was married to someone else when she was born.) A Dyker Heights princess in a white Mercedes, she had a peculiar set of teen dating woes. “Guys I wanted to go out with didn’t want to go with me,” says Schiro. “They heard the rumors. ‘Don’t go out with Linda. Shit happens.’ They put a beating on one boyfriend and tossed him in the road because I got caught drinking with him.”

McLaughlin wasn’t exactly her thing: pale, blue-eyed, Irish. But her parents liked having him around. He’d sit on the Scarpas’ living-room couch watching TV with Linda and her mother, until he was dispatched to deliver a message or find someone Scarpa wanted to talk to.

Linda’s father tolerated behavior from McLaughlin that would earn other guys a beating: When she walked through the room in a bikini, fresh from the backyard pool, the other guys respectfully looked away. McLaughlin stared. “My father would swat him on the back of the head,” she remembers. Tommy Gioeli warned his young cousin about Greg Scarpa. “He thought my father was too crazy,” says Linda. She says her father and Gioeli were competitive over McLaughlin – his allegiance and muscle. “They were fighting over him since he was a teenager,” she says.

In November 1991, an internal war broke out between two Colombo factions – the Scarpa-led crew that was loyal to Carmine Persico and the upstarts led by street boss Vic Orena. When a van full of Orenas ambushed Greg Scarpa in his driveway one morning, he narrowly escaped, plowing his Lincoln through the gunfire to safety. McLaughlin was among the first to congregate at the Scarpa home that evening, wielding a .38 and vowing revenge.

It was only a matter of time before someone got to McLaughlin, too, and the following June, his own Lincoln was ambushed as he drove through Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. One bullet grazed his back; McLaughlin and his passenger ran for their lives. Another shot severely injured a 16-year-old bystander sitting on a park bench nearby. McLaughlin turned up later at Scarpa’s house, still bleeding. The two would-be assassins were brought to trial and convicted on witness testimony, but McLaughlin refused to cooperate with police.

By 1992, McLaughlin was moving ounces of cocaine from his sister’s Staten Island condo to the street corners of Bensonhurst. The Brooklyn DA’s office was already onto him. A four-month wiretap on his phone captured three separate incidents of McLaughlin delivering two-plus ounces of coke to his undercover snitch.

By September of that year, Ierardi and Rodriguez were ready to make their move, but just then, the Colombo fighting heated up and drove McLaughlin underground.

They waited for him to resurface, and a few months later, they got a tip that McLaughlin and other mob associates would show up at the wedding of a fellow Colombo member at the Embassy Suites in Brooklyn. One of the guests, a local cop from the neighborhood, volunteered to wear a wire and alert Ierardi’s team when McLaughlin and the others arrived. But the cop got drunk and soon blew his cover. “He was talking into his lapel, and they all saw him,” says Ierardi. McLaughlin, who had brought Schiro as a date, spotted the cop first and told her, “‘I need you to cover for me because something bad is going to happen,'” she recalls. When the local cop approached her, she pointed him in the wrong direction while McLaughlin climbed out a bathroom window. “That was the last I saw of him before he went to jail,” Schiro says.

They finally caught up to him in December, at a Christmas party at a bar in Dyker Heights. Ierardi and his team grabbed him at the bar, pinning McLaughlin facedown against a table. Finally. McLaughlin would be crucial: If they could break him, they could bring down bigger fish.

These weren’t bullshit charges he faced – racketeering, extortion, firearms, drug trafficking, and tax evasion – more than enough to put him away for a long time. Rodriguez and Ierardi tried to flip him, getting McLaughlin to offer names in exchange for leniency, but he wouldn’t budge. The usual psychological pressure points had almost no effect on him. He had very little family of his own, and any real obligations he felt were to Scarpa and his crew. “He pretty much told us to pound sand,” says Rodriguez.

McLaughlin dodged some charges, but admitted to one charge of selling coke and one of tax evasion, for which he got 14 years in prison, to run with nine years he’d been sentenced on his state charges. By then the war was over. Scarpa had died, in June of 1994, of complications from AIDS. When Linda’s brother Joey was killed the following year, she turned to McLaughlin, who was then serving the state portion of his sentence in Green Haven Correctional in upstate New York. “It was the worst time in my life,” says Schiro, “after my father died and my brother got killed too. And Tommy reminded me of them both.” In 1996 she secretly married McLaughlin in the prison visitors room.

At first, McLaughlin promised to reform himself while in prison. He talked about taking courses toward a GED and got a job working as a porter. Schiro visited him in the prison’s on-site family housing, a small place near the exercise yard, bringing along baked ziti and chicken parmesan that McLaughlin’s sister, Joanne, cooked for their weekend together. “He was trying really hard to have this nice time alone with me,” she recalls, “without the other inmates on top of him and stuff.”

The relationship was good for a while, she says, because McLaughlin refused to talk about mob life or the people he knew on the outside. “He was saying he was not going to get involved in all the prison bullshit or people doing crimes on the inside,” she says. But it didn’t take long before McLaughlin’s temper resurfaced, or his fists were called upon for protection or to settle scores for other mob guys inside. “I wouldn’t hear from him for two weeks, and then he’d surface and I’d say, ‘Where the fuck have you been?'” she says. “And he was in the hole, or had his privileges taken away for fighting.” Soon, every conversation they had revolved around grudges with inmates and guards. “He became a prisoner,” she says. “He had a prisoner’s mentality.” Schiro stopped visiting and calling. McLaughlin stopped calling too. She filed for divorce two years later.

Before Tommy McLaughlin started wearing a wire for the FBI, he needed to be taught everything about being a snitch. Agent Seamus McElearney likes to say that handling an informant is “like having a newborn.” McLaughlin’s handler, Scott Curtis, a West Point grad who has flipped several wiseguys in his 13 years on the FBI’s anti-Colombo squad, taught the ex-con how to operate his wire (sources say it was in his watch) and how to meet up so they wouldn’t be seen. He schooled him on how to turn a vague confession into admissible evidence and laid out the ground rules on what kind of criminal acts he could and couldn’t commit while working for Team America. He could loan-shark, for example, or run a gambling club, but he could not commit any violent acts – especially not murder.

The first stumbling block for Curtis and McLaughlin’s other handler, Russ Castrogiovanni, was his living arrangement. He shared a house in Staten Island with another mobster, Peter Tagliavia, an old friend and fellow inmate who was now married to his sister. So Curtis flipped him, too. And the brothers-in-law formed an informant tag team that recorded the daily workings of the Colombo syndicate like the minutes of a shareholders’ meeting.

Their wires captured crimes of loan-sharking, extortion, labor racketeering, the planned bribery of a state official, admissions of murder, planning for secret induction ceremonies, and a soundtrack of street violence compiled along the way. Working as a plant is a risky, stressful, and dangerous business, and it creates a shaky alliance. It relies on the mutual trust of cops and criminals, who had formerly been sworn enemies – all capable of elaborate misdirection, obfuscation, and shifting loyalties. The informant has to amass admissible evidence, ideally without getting too involved himself. But for a mobster who is betraying his longtime associates – in some cases lifelong friends or rivals he knows he’ll never see again (except, maybe, in a courtroom) – it’s a chance to return favors, settle old scores, even make a little extra in the process.

If educating McLaughlin on being an informant was like having a newborn, it didn’t take long for McLaughlin to grow into a rebellious child. “He’s out there creating criminal activity and enjoying himself,” says a defense attorney who has listened to dozens of hours of McLaughlin’s tapes. McLaughlin didn’t kill anyone while he was wearing a wire, but the no-violence rule may have been harder for him to adhere to. The fact that he was being recorded by the FBI did little to curb his impulses. The Colombo family frequently relied on McLaughlin’s muscle, enlisting him on collections or, for example, to bust up a rival after-hours gambling club. But even as he acted the part of the loyal mob thug, he also created opportunities to rack up charges against his colleagues. At one point, he reportedly urged Anthony Russo (a highly placed capo and the main target of his undercover work) to renege on an agreed restitution payment to a Colombo associate who had been partially paralyzed by a Gambino knife. McLaughlin’s solution, according to one defense lawyer who has heard the tapes: “When the money comes down, why don’t we just kill this shit kid and put the money in our pockets?”

Defense lawyer Mathew Mari says McLaughlin and his handlers were playing a dangerous, legally dubious game. “The truth is,” says Mari, “you have very capable people here, and to tell them to do something like that is like telling a mad-dog killer, ‘Sic ’em.'”

In one case, defense lawyers claim, McLaughlin participated in a vicious brawl, showing up at a Bensonhurst bar armed with baseball bats and beating on a patron who’d been annoying Russo. It’s all captured on tape. “You can hear the aluminum bats banging” amid the shouting and yelps of pain, says the defense source. “Tommy is a dangerous kid,” says one defense lawyer. “He can’t stop himself, and no one can control him. Tommy is a legitimate badass – shoot you, hit you with a bat, knock you with his fists. He’s like that psycho character in The Town. He’s nuts.” The feds contend that McLaughlin was trying to minimize the violence at the scene.

FBI protection included a few perks, including the loosening of McLaughlin’s probation rules. He took FBI-sponsored out-of-state trips, which allowed him greater mobility and freedom beyond his curfew. Not that he couldn’t find trouble during tamer hours. One night at a Bay Ridge nightclub, McLaughlin took on a testy parking valet he said was mouthing off to patrons. He punched the guy in the head, which was all caught on his wire. He was arrested for assault, a charge that was eventually dropped, but he didn’t get off completely. Not included in the FBI’s hundreds of hours of McLaughlin-generated tapes are the hours he spent in weekly anger-management classes.

By last November, Anthony Russo had started to get suspicious. The Colombos were forced to call off a secret induction ceremony when they spotted McElearney’s guys clocking the house where it was to take place. Russo sensed the feds were closing in. He told McLaughlin there was a “rat real close to us,” telling the informant that he wanted to find the rat and “chop his head off.” A little more than a month later, satisfied they had the evidence they needed, the feds placed Tommy McLaughlin and Peter Tagliavia and their families in protective custody and arrested 127 suspected mob associates, soldiers, and capos from Florida to Rhode Island.When Tommy McLaughlin takes the witness stand, as he’ll likely do in a Brooklyn federal court this month, the first thing he’ll need to do is tell the jury the worst things he’s done in his life. Primary among them is the 1991 murder he was an accomplice in, the one that flipped him in the first place. In telling the story, he’ll finally be publicly professing his guilt, but he’ll also be sealing the fate of his cousin Tommy Gioeli, the former acting boss who sanctioned the hit.

Though he has pleaded innocent to all charges, Gioeli will face trial for five other murders, including the 1997 shooting of an off-duty police officer, gunned down outside his home because he’d married a Colombo consigliere’s ex-wife. Gioeli’s trial will probably include testimony from a wide array of Colombo turncoats, some of whom, including Russo, were ensnared in the January raid. (Thirty-three of the 48 have already cut plea deals and collectively have forfeited $4.5 million in illegal proceeds.) The trial will serve as a dramatic and grisly curtain raiser to a series of trials of the Colombos and other crime families in the months to come.

McLaughlin himself will be looking for a deal off the backs of the friends and family members he’s betrayed.

It’s unlikely he’ll be out on the streets – even ones far from Brooklyn. McLaughlin pleaded guilty to the 1991 murder under what’s called a John Doe arraignment and will probably be sentenced after prosecutors have squeezed him for every bit of testimony they can – not just on the Colombos but on the Gambinos, Bonannos, Luccheses, and any other Mafia organizations. He’ll probably get time in a special secure federal prison for informers. It’s not going to be an easy and carefree life.

Near the end of summer 2010, a few months before the big mob takedown, Linda Schiro was driving through Staten Island when she spotted a guy she recognized. He was standing at an ice cream truck. It was McLaughlin, whom she hadn’t seen in 10 years. “He looked the same, but his hair had gone gray,” she says. She pulled up alongside him and called out. He froze, turned around “and looked like he’d seen a ghost,” she says. “He was real nervous talking to me.”

Schiro says she thinks she understands why McLaughlin chose to flip for the feds. “He pretty much said, ‘I’m never going back there again,'” says Schiro. “He should have done it the first year they got him. Could have saved himself 14 years.”