The Little Engine that Could

DETAILS MAGAZINE

FEBRUARY 2007

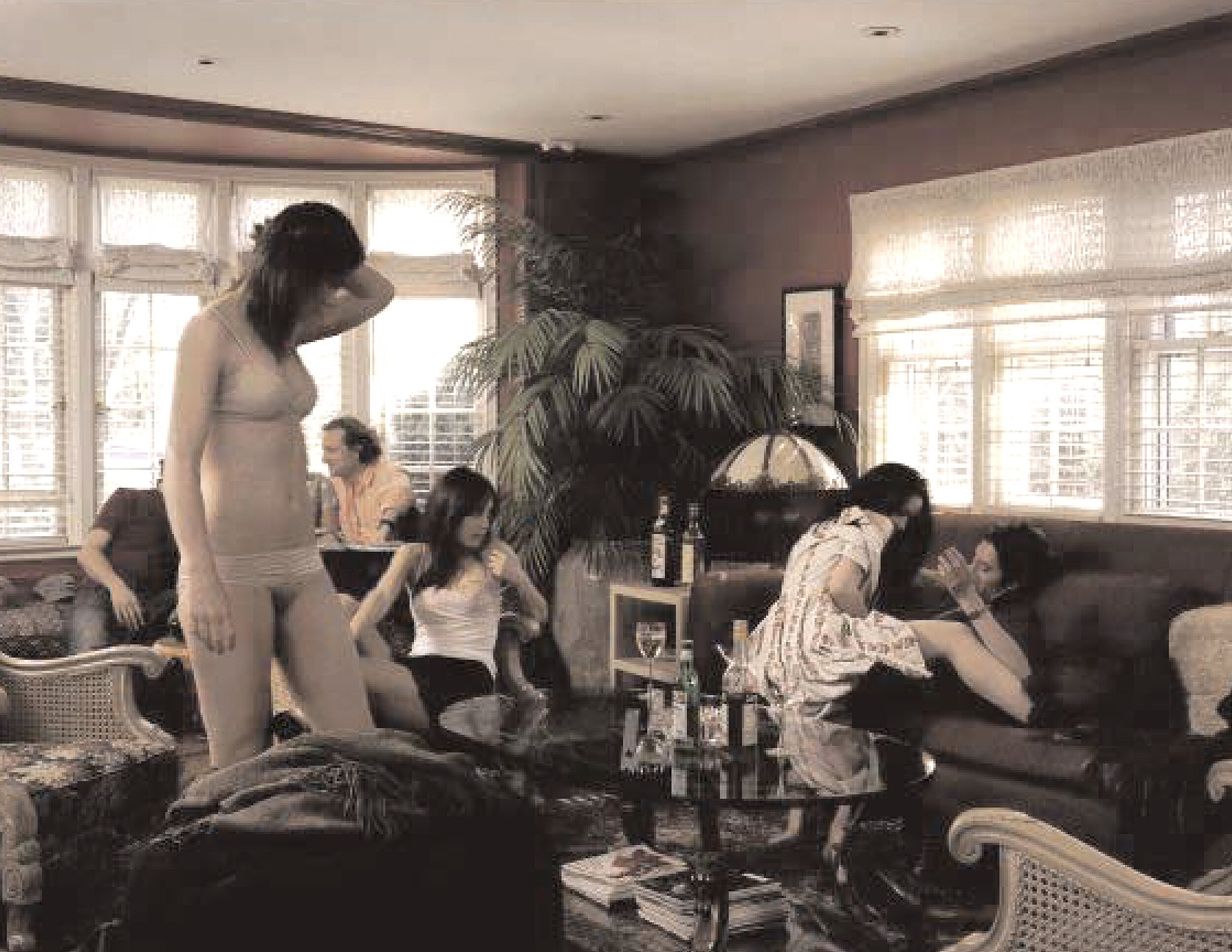

Photo by Michael Lewis

As google gears up to go public, the words Internet start-up and profitability may finally go hand and hand.

IF THESE PHRASES HAPPEN TO BE SKITTERING ACROSS YOUR BRAINPAN, you’re probably a sadistic, soccer-playing, pop-star-loving pervert. Or maybe you’re a sky-gazing Jersey construction worker with a taste for Hindu holidays.

Or maybe you’ve just set foot inside the collegian Mountain View, California, headquarters of Google.com, the astoundingly successful, three-year-old search engine that’s come to a boil during the dot-com bust. Here, amid 100 lava lamps, the obligatory foosball tables,pyramids of Trix and Power Bars, and a player piano (Clapton’s “After Midnight” is a favorite for all-nighters), such real-time Web queries—the sort of random searches that turn up 1,800 times a second on Google.com—are projected like film credits onto a white lobby wall, a nonstop Cartoon Network gloss on interior decorating.

Google’s office slide show represents just one of the many things its nerdy founders do for kicks. “People are pretty creative and wild here,” says co-founder Larry Page, 28, a shy tinkerer who once made his staff wear pink Afro wigs to a toplevel meeting.“We just kind of hang out.It makes people less on-edge.”

While other members of the dot-community associate edge with burn rate and plunging revenue, Google is thriving as if the bubble never burst. Here, it’s 1999 all over again, and a visitor might as well be a tech Van Winkle. Where are the pink slips? The auctioned Aeron chairs and mochaccino makers? Where are

the CFOs turned taxi drivers? Where’s the recession-tightened fear?

Definitely not here. Google, with its stark look (no banner ads or flashy graphics) and its elegant ability to pluck useful information from the Web’s daunting tangle of pages, had 2001 revenues estimated at $50 million, and is reporting two straight quarters of solid profits.Beyond its increased earnings, Google has accomplished something enjoyed by only the most successful companies: Its brand has become a verb, thus enriching the language. All across America, at any given moment, it’s a safe bet to say that someone is Googling somebody. As in:“ That asshole Googled me,s o I broke up with him!”

Since its launch in 1998,Google has become the top “pure” search site on the Internet—handling some 150 million queries a day—and the fifteenth-most visited site on the Web, according to Jupiter Media Metrix. Experts say the company could become a $1 billion business.Google’s founders are considering an IPO sometime this year.

“There’s no question they’re doing the best job out there,” says Danny Sullivan, editor of searchenginewatch.com. “Right now, no one can stop them. And they know it.”

THAT SWAGGER CARBONATES THE ATMOSPHERE AT THE GOOGLEPLEX, AS headquarters is known to Google’s 270 employees—or so it feels when I arrive on a recent Wednesday morning to find out how a pipsqueak start-up launched by two Stanford University grad students muscled in on a $2.9 billion ad

market dominated by the likes of Yahoo, Lycos, and Excite.

Page, a doe-eyed Michigan native with impressively thick eyebrows and a Buddhist’s poise, has been buried in his office all morning, amid toy robots and a wooden parrot that hangs from the ceiling. He shares the space with Google co-founder Sergey Brin, 28, a gymnast-fit Soviet emigré with wiry black hair and a brainiac’s high forehead.With wrinkled shirts and jackknifed jackets tossed over the camel-colored leather couch and a pair of K2 skis jammed into a corner, the office looks like a dorm room. But few campus crash pads ever held quite this kind of gray matter or this much non-alcoholic philosophizing.

“In a sense, we’re assembling the world’s biggest library,” says Page, absently pushing a toy Volkswagen Beetle across the lone stretch of clean desktop. “How do you get access to everything? Can you make sense of it? Can you organize it?”

Google’s founders have crashed hundreds of all-nighters pondering these questions. Along the way ,they’ve indexed 2.1 billion Web pages, more than any other search site. Google’s success, though, depends not just on its size but also on its speed and accuracy.

Most search engines crawl the Net with software “spiders,” which match a query by counting the number of keywords on a Web page, and return thousands of results. But they often have no idea which results are significant—or which sources are most respected.Google not only looks for keywords but also ranks a page’s importance by counting the number of sites linked to it. As for speed, Google returns results in a split second; its text-driven pages freeing swaths of bandwidth that are devoured by graphics on other sites, a welcome time-saver for dial-up users. The result is that you get what you need.

“They really have a sophisticated system,” says Scott Gatz,general manager of search and directory at Yahoo, which licensed Google’s engine in July 2000 to enhance its own searches. (Yahoo also bought an undisclosed equity stake in the company.) When Yahoo can’t find a match for a query, it defaults to Google.

The Yahoo deal catapulted Google from digerati darling to mass-market obsession, helping its daily query load more than double last year. In 1998, Yahoo could have snapped up Google for a handful of stock. But when the Googlers showed up on their doorstep, the Yahoo gang suggested they keep working on their little school project—and come back when they’d grown up.

LARRY PAGE IS THE SON OF A MICHIGAN STATE COMPUTER-SCIENCE professor. When his older brother gave him a set of screwdrivers, Page, then 9, set out to dismantle any power tool he could get his hands on, annoying his parents when he couldn’t put them back together.

“I wanted to be an inventor,” he says,his sloping shoulders framed against a courtyard oasis of palm trees and a man-made brook visible from his second floor window. Page developed an early fascination with Nikola Tesla, inventor of the induction motor, who barely made enough money to support his work.

“I was really affected by that,” Page says, meeting my eyes, briefly, for the first time.“ And I knew I wanted to invent things that would be useful to the world— and that I would make money at.”

Sergey Brin had similar DNA. He fled the Soviet Union at 6 with his mathematician father and his mother, who now develops computer weather models for NASA.The Brins bought their son a Commodore64 computer when he was 9; he quickly found himself hooked on math and physics.

In 1995, when the two computer-science Ph.D. candidates met up at Stanford, Brin was already working on data mining, digging for patterns in vast reams of information. He was searching, he says, for “relationships” that would be useful in academic research. Page was so intrigued by the work that he, too, began digging for data in the Web’s ever-expanding cosmos.

By January 1996, the pair had pooled their brainpower and begun work on a search engine that they playfully named BackRub, for its system of analyzing the “back links” that point to a particular Web site. They used several Stanford computers to set up a search engine; their professors and peers started tapping into it shortly thereafter. Page and Brin soon settled on the name Google—a play on googol, which refers to the number represented by “1” followed by 100 zeros.

As demand for their new search engine spread through campus, Page and Brin realized they needed more hardware to handle the load. They began lurking on Stanford’s loading dock,snatching unclaimed computers. With $15,000 worth of credit cards, they set up PC servers in Page’s dorm room. Page and Brin knew they were on to something big, but two years passed before they started their company, mainly because, quaintly enough, they wanted to finish their Ph.D.’s first.But by the spring of 1998, their humble engine was handling 10,000 queries each day, and the entrepreneurial momentum was too strong. “It became unreasonable to keep it in the department,” Brin recalls as we sit across from each other at a lunch table. And so they began shopping their nascent technology to several major search players, including Excite and AltaVista. They were turned down cold.“They all said,‘We’re a media company—we’re interested in content, not search,’” says Page. “This really inspired us to work on it ’cause we realized that nobody else was.”

Graham Spencer, a founder of Excite and its former chief technology officer, says Excite did consider licensing Google in 1998 but felt that its own search worked just fine. “There was a belief in the industry,” he explains, “that search was tapped out. In hindsight, focusing on search was clearly a great move for Google.”

Around the same time, a Stanford professor introduced Brin and Page to Andy Bechtolsheim, the famed Silicon Valley technologist who helped found Sun Microsystems. He heard their pitch on the professor’s Palo Altoporch one morning; within minutes, Bechtolsheim cut them a check for $100,000 to build a server farm, a decision he calls a “no-brainer.”

After raising another $1 million, the duo set up shop in the Menlo Park garage of a friend. Traffic spiked quickly as tens of thousands of techno-geeks on the hunt for new tools started sniffing at their site. Impressed, Bechtolsheim brought in two top Silicon Valley venture-capital firms, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers and Sequoia Capital, funders of Apple, Cisco, Compaq, and Yahoo. In the hot tech climate of June 1999,they soon raised $25 million for Brin and Page; their funding would plateau at $35 million.

Page and Brin, of course,won’t say, but during the Internet heyday savvy founders typically retained a 50 percent or higher stake in their start-up, meaning Page and Brin could be sitting on hundreds of millions. Page, reclining on an office couch with a Blackberry hooked on his belt,is coy about the whole thing. “I

was very happy with the deal,” he says simply ,“and I’m still happy with it.”

SERGEY BRIN IS CHEERLEADING LIKE A CAMP COUNSELOR ON AWARDS day. His torso is sheathed in a pec-hugging T-shirt as he stands in front of a maze of beige cubicles holding a microphone to address a packed room of 70 or so employees sipping Sierra Nevadas and Anchor Steams.

Brin goes through a list of the week’s accomplishments, thanking by name every person who worked on a new product or site feature. Today’s most exciting news, he says, is the alpha version of a new ad enhancing feature. “What are we gonna get out of this?” he asks, as Page smiles nearby. “Does anybody know?”

“Ads!” yells a man in baggy shorts and a tie-dyed T-shirt.

“Money,” says a woman.

“Well, we’re already getting money now,” says Brin.

“More money!” several people shout. The room breaks into applause.

Users are often surprised to hear that Google gets three-quarters of its revenue from advertising. This is because instead of selling banner ads, Google sells keywords. Ads appear discreetly above the rankings and run down the side of the page. Such targeted text ads, says Brin, outperform banners—they’re relevant to a user’s search, offering a URL and a useful two-line description of the site.

“You want information based on what you searched,” Page explains. “So we’re really lucky. We know 150 million times a day exactly what someone wants. You give them that thing, they’ll look at it, they’ll buy it.”

Such user-targeted ads help marketers measure the impact of their spending, which is why these ads are selling increasingly well, even in the current slump. “A company like L.L. Bean can say, ‘We made back three times our ad budget,’ and they’ll increase their buy.”

“Google’s rate of click-throughs averages more than 2 percent,” says Page—compared with the industry standard of 0.5 percent on banner ads.The company charges advertisers $30 to $40 for 1,000 click-throughs. “Google has really challenged the business model,” says Lydia Loizides, an Internet analyst at Jupiter Media Metrix.“But they’re facing the same challenges as everybody else now.”

Though most of the big search sites also sell keywords for targeted ads, Google has been hurt less by the slowdown because it was late to the game, ramping up its ad program just as the tech market was tanking. “It’s not like we were used to having a huge revenue stream,” says Brin. “So we haven’t really taken much of a hit.”

In fact, Google has also been frugal. It relies solely on word of mouth. That buzz, especially among the industry’s top technologists, has also helped Google grab lucrative contracts to manage the search technology of 130 other companies, including Cisco, Sony, and Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia. Such deals now account for the other 25 percent of Google’s revenues.

LAST AUGUST, IN A SIGN THAT GOOGLE WAS APPROACHING MATURITY, Page and Brin relinquished management to famed Silicon Valley suit Eric Schmidt. “We were looking to not screw this up,” says Brin as we dig into smoked salmon and pepper-crusted top sirloin on a sun-filled porch outside the company cafeteria. The noodling strains of Jerry Garcia play in the background. “Basically, we needed adult supervision.” Brin adds that the board of directors, two of whom belong to their VC team,“feels more comfortable with us now. What do they think two hooligans are going to do with their millions? Oh, my God.”

Schmidt, 46, may seem an odd choice to run Google. A one-time chief technologist at Sun Microsystems, he was most recently the CEO of troubled software maker Novell (his only stint running an entire company), which lost market share during his four years at the reins and continues to bleed red ink. Schmidt has said he was “in over his head” at the billion-dollar firm.

“The company was sort of nearing bankruptcy when I got there,” Schmidt says. “Overall, I don’t have any regrets.But I might have done a few things differently.” Schmidt hopes to push Google deeper into the lucrative corporate-search field and to help grow it overseas as well. He’ll also oversee acquisitions and hire a C.F.O. Schmidt, who bought an undisclosed stake in the company, will have the helm when Google goes public, though he’s not sure exactly when it will happen.“ The consensus is that we probably should wait.”

Ironically, if Brin and Page started a year earlier,they would have certainly gone public by 1998 and seen their stock mushroom—and then collapse like every other dot-bomb. “The investors would be pissed off, the bankers would be pissed off, and the employees would be pissed off,” Brin says.“In a sense, we’re lucky.”

WHEN GOOGLE ULTIMATELY DOES GO PUBLIC, ITS DOT-COMMANDO culture—in-house gym, on-site doctor, free lunches (cooked by a former chef for the Grateful Dead), and daily massages—will surely fall under the kind of scrutiny that comes with exposing your books. But Google is not loafing: With a brain trust of 50 Ph.D.’s on staff, it’s currently at work on 30 new projects, including a push into wireless partnerships with firms like Handspring and Palm, and even a deal with BMW to feature voice-activated search in its highend sedans.

But even as Google pushes into new arenas, skeptics still wonder whether search alone is a viable business, a notion that makes Brin wince. “The theory that search isn’t sustainable was wrong in the past, as we’ve proved,” he says, with an assurance that verges on arrogance. In fact, Brin predicts that Google’s revenues will double next year. “Along with e-mail, search is ten times more important than any other service on a portal.”

Google also finds itself in an odd conflict of interest, threatening some of the companies that license its technology. Why, for instance, would anyone bother going to Yahoo to search if Google is giving them a better experience? Brin and Page have pondered this delicate question (which is regularly raised

in meetings with prospective clients) and fashioned a diplomatic answer.

“We’ve always made it clear that we’re solely a search destination—not a portal,” says Brin. “And we manage those relationships by building trust.” Yahoo, for its part, certainly agrees. “I don’t see this as a competitive situation,” says Yahoo’s Scott Gatz. “I think it’s a complementary one.” Gatz won’t disclose

how much Yahoo pays Google or how large its stake in the company is. He also won’t rule out the possibility that Yahoo will turn to another search company in the future. “We’re always keeping our eyes open,” he says.

Meanwhile, Google finds itself suddenly crowded by upstarts garnering the same kind of buzz Google enjoyed in its infancy. Two of the top contenders include WiseNut.com and Teoma.com. Both have borrowed Google’s clean look; both use keywords and links to find relevant pages.Unlike Google, they

not only measure the quantity of links but also look for “peer” links from similar subject pages. And both—also unlike Google—categorize results on the first page, placing matches in subcategories for easier review.

Page insists the competition still has a ways to go. According to him, the upstarts haven’t indexed anywhere near the number of Web pages, and they’re not even close in terms of traffic. As for bells and whistles, he cites Google’s handy spell check (misspell a word and Google suggests a correction). Ultimately, however, Page claims he’s in competition not with other companies but with technology itself. He dreams of the ultimate search engine: something that could handle complete questions—not just keywords.

“That means you’d basically be able to say, ‘What should I ask Larry Page in this interview?’” he says, leaning back behind his desk. “We’re nowhere near that kind of sophistication. But we do have people working on very speculative things that would push the envelope.” Then, revealing a trace of competitive

spirit after all, he adds:

“There is no one else who has anything close. Eventually, people might catch up with us—but by then we’ll have something even more important.