Crash and Boom

NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

MARCH 16, 2012

On a rainy Saturday night in Lisbon, A Vizinha, a rustic cafe lined with tins of sardines and sacks of rice, was packed with the city’s young style set — new-media girls in baggy sweaters and floral scarves, skinny boys with fussy facial hair and engineer caps. They had come here, to Bica, a grubby hillside neighborhood, for a show: an organist, David Maranha, and jazz drummer, Gabriel Ferrandini, were churning out a chaotic and deafening soundscape. It growled and hummed, shrieked and snapped, above a single-note drone from a maxed-out little amp.

The crowd, mostly unemployed 20-somethings, was drinking red wine, nibbling hard-boiled eggs and rolling cigarettes. Some spilled out onto a narrow cobblestone street. When a tram glided by, they crammed onto the sidewalk and flattened against the storefront’s windows, then exhaled back into the street, nursing half-empty glasses and nodding to the rhythm. It was the perfect soundtrack for an apocalypse.

“The crisis has everyone thinking, ‘How do we survive? How do we make something of all this?’ ” said Adriana Sá, a musician and composer who had begun holding the regular gathering, called Sabaduo, a week earlier. “It reveals the spirit of the people. Here I am earning nothing. Who cares?”

Portugal’s recession, one of the worst in the euro zone, has hit its youngest citizens the hardest. The unemployment rate for people aged 25 to 34 hovers at about 28.5 percent, which is more than double the national rate of 13.6 percent, already one of the highest in the region. But rather than rioting and setting streets on fire, young Portuguese are turning their anxieties and frustrations into a flourishing D.I.Y. cultural scene in the capital. It’s a largely improvisational movement and, to some, an unexpected one: last year, to help meet the terms of a $103 billion international bailout, the center-right coalition government dissolved the culture ministry, the lifeblood of the country’s artists. Since then, they’ve been turning to each other instead of to the state.

“One positive thing the crisis gives us is events like this,” said Rui Costa, a sound artist and filmmaker who also runs an artists colony. He was seated at a window table at A Vizinha across from his wife, Maile Colbert, a multimedia artist who had moved from Los Angeles. “There was this idea that the state supports the artist. That created competition for grants and access where there should be community. Once that fails, you have to build stuff from scratch.”

Young Lisbon is indeed building like crazy: there is street art on decaying walls, experimental theater at the harbor, raves in old canneries. Everywhere, the anything-might-happen energy has spurred a desperation to create. Even the city has gotten into the act, setting up public walls as canvases and opening the Galeria De Arte Urbana to archive the graffiti.

For Maranha, the organist, playing in a pop-up space and drawing people in from the street adds to the urgency of his music. “It’s great that people are out wandering around looking for the new,” he said, still sweating from his 40-minute set. “It’s as if the crisis has made people wake up and say, ‘I have to get out to the street.’ ”

Lisbon has long been one of the prettiest cities in Europe. Its pitched hills and valleys are like a Mediterranean-flavored San Francisco, and the streets seem to wear art on every surface. Beaux-Arts buildings are sheathed in Moorish tiles of bright blues and sunset reds; the sidewalks, too, are covered in mosaics.

Before it spread, the city’s street-art scene was concentrated in Bairro Alto, a hilltop bohemian neighborhood that was home to punks, metalheads, goths, gays, writers and artists in the 1980s and ’90s. The winding quarter still has the best bars, cafes, galleries, restaurants, boutiques, gay clubs and discos. On weekends, thousands cram the area, less to create than to get drunk or high on Portugal’s decriminalized drugs.

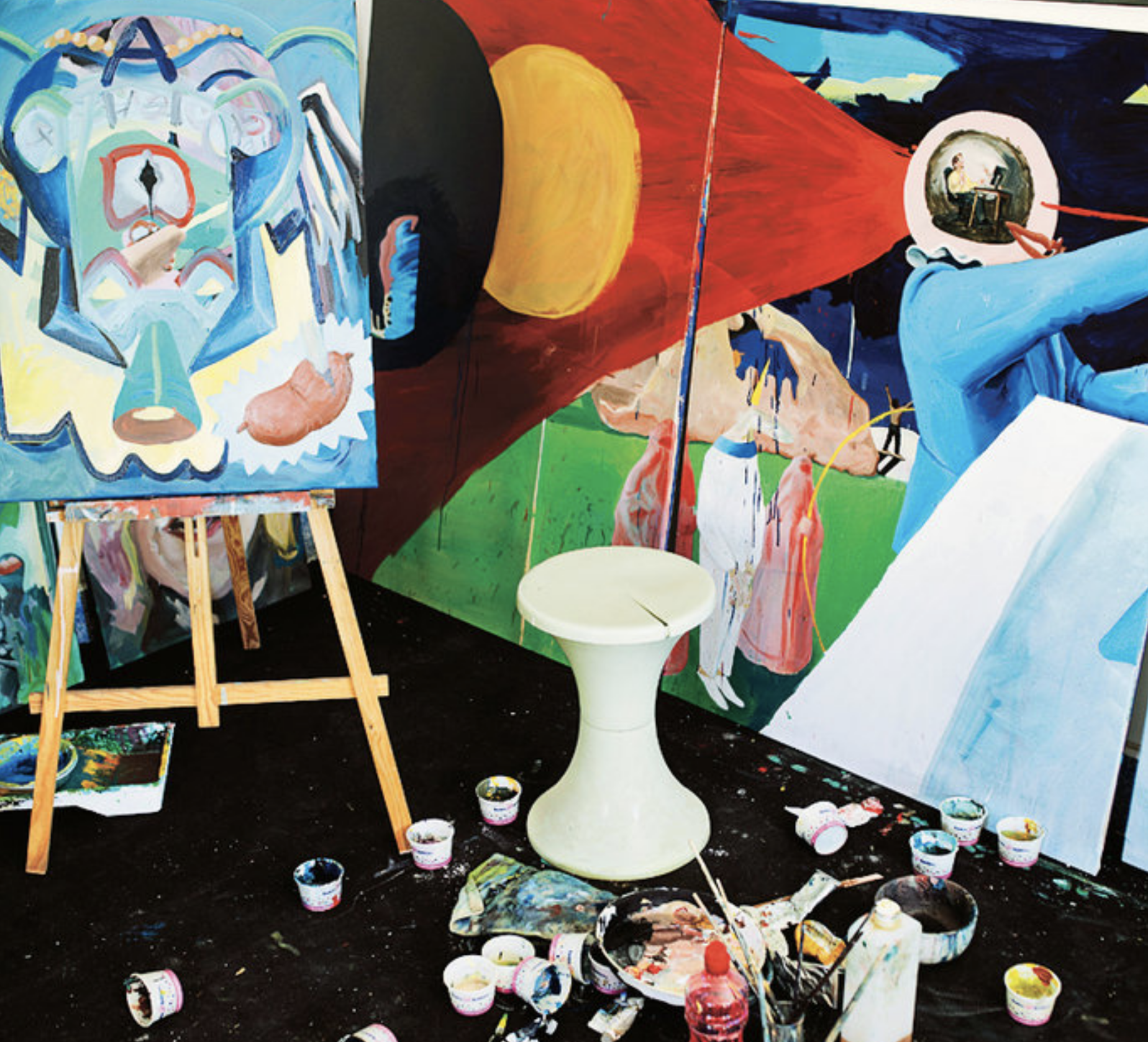

On a recent chilly afternoon, Bairro Alto was deserted. But its best-known cultural landmark, Zé dos Bois, a nonprofit arts group housed in a 17th-century palace, was clattering with activity. ZDB exhibits visual art and modern dance, puts on raves in its first-floor bar and offers residencies for contemporary artists. Inside, half a dozen young men in ratty sweaters and paint-splattered denim were working on its drafty top floor — painting canvases, building camera obscuras, programming beats on MacBooks. All were from local art schools, and all had their sights set on galleries and museums. The organization’s visual arts director, Natxo Checa, explained that the financial crisis has cratered local art buying, but it has actually been good for art. “It’s become difficult to produce works, promote them and create visibility,” he said. “But it has strengthened our intellectual side. It gives people time to think and time to read and be awake to the world. We are all thinking, ‘What is our art? Who and what is it about?’ ”

Checa says the uncertainty harks back to a period a generation ago, after the 1974 revolution ended 40 years of dictatorship and brought an outpouring of radical art into the streets. Large-scale posters depicting united workers sprung up throughout the country, particularly in Lisbon. A decade later, when foreign capital and ideas flooded the city, the posters had to vie with Western advertising. And as the years wore on, they stood testament to the revolution’s fading ideals.

Alexandre Farto was a teenager in the 2000s, and the remnants of those riotous images transfixed him. Now 24, Farto, who goes by the tag “Vhils,” is a renowned street artist. (His work has appeared alongside Banksy’s at the Cans Festival in London.) “The posters from the revolution were completely crumbled,” he said, speaking by phone from his studio on the outskirts of town, where he was preparing for a solo exhibition at Shanghai’s 18Gallery. “It was kind of poetic and at the same time melancholy. You had these advertising billboards competing with this old message, or completely covering it up. It reflected how fast we were changing and our values were changing.”

“It’s great that people are out wandering around looking for the new,” he said, still sweating from his 40-minute set. “It’s as if the crisis has made people wake up and say,

‘I have to get out to the street.’ ”

The revolutionary art inspired Farto to begin carving portraits into the sides of decayed buildings. In 2009, after Portugal’s housing bust left rows of speculative apartment projects empty near Lisbon’s center, Farto convinced the city to let street artists paint over four of the buildings. The result, called the Crono Project, runs along one of Lisbon’s main arteries, the Avenida Fontes Pereira de Melo: a four-story-high alligator, a sickly-looking crow, a Matisse-like shadow thief and, most disturbing, a bloated and bug-eyed humanoid wearing a crown of oil company logos. “No one wants to look at them,” Farto said of the abandoned buildings. “This was a way of pointing a finger, so people have to look.”

A 2008 tally found that Lisbon contained some 4,000 abandoned buildings. After dark, it can seem like a ghost city. Everywhere you walk, whether it’s the historic and fashionable Chiado shopping district or the medieval Alfama quarter, you’ll find boarded-up windows, grass growing on roofs and full bushes sprouting from walls. In Alameda, a working-class neighborhood of tiled buildings, government-erected hulks and ground-floor butcher shops, many apartments remain empty.

On a Sunday evening, five young artists gathered in one such Alameda apartment, their faces lit by an open MacBook. The men had recently formed an art collective, Orfeu, and produced one of the most memorable shows of the year. Held in a former glass factory nearby, it showcased 40 artists and four musicians and drew a word-of-mouth crowd of 800. Now, rain coming down outside, they were scouring Google Maps for an abandoned building where they might hold their next show. The apartment in which they were meeting is owned by one of their friend’s grandparents; they have made it their headquarters. The room was thick with cigarette smoke. Paintings and lithographs were stacked in the corners.

One of the men, Sérgio Faria, a 23-year-old product designer and music producer, explained the need for a group like Orfeu. (The name, Portuguese for Orpheus, is an homage to the Grupo de Orfeu, a collection of early Modernist writers and painters in Portugal in the 1910s.) Faria said that most of the 40 artists and designers exhibited at the show had never shown their work in public before. With so many galleries closing, few of them had found a way to reach collectors, and many felt their reliance on social networking had isolated them. “I have all these friends on Facebook who are artists, and no one is showing their work,” Faria said. “You’d have a blog where you showed your work, and I am sick of blogs. You want to go to the physical world and see the work.”

Lisbon’s new creative energy might best be epitomized by Faria. A soft-spoken man with a dark beard, a knit cap on his head and a plug in his left earlobe, Faria created the soundtrack for a short film in a celebrated series about the city’s underground scene, “Lisbon Youth,” by the videographer and artist João Retorta. Faria lives with his parents, as do the other members of Orfeu. He is getting his master’s degree in product design and trying to land a state-sponsored internship at a company in London.

“I’d rather stay here in Lisbon because I love Lisbon,” he said. “I wouldn’t even be getting a master’s degree if there was work for me to do here.”

Faria asked each friend if they had jobs, and they all shook their heads. “Finding a job in Portugal is crazy,” he went on, as the others turned to listen. “I don’t want to work in a cafe. For me that’s valuable time, that’s time I can use to create. This is why we have Orfeu. I don’t want to fight for a job in a cafe that I don’t want.”