Mommies Not Required

DETAILS MAGAZINE

AUGUST 2006

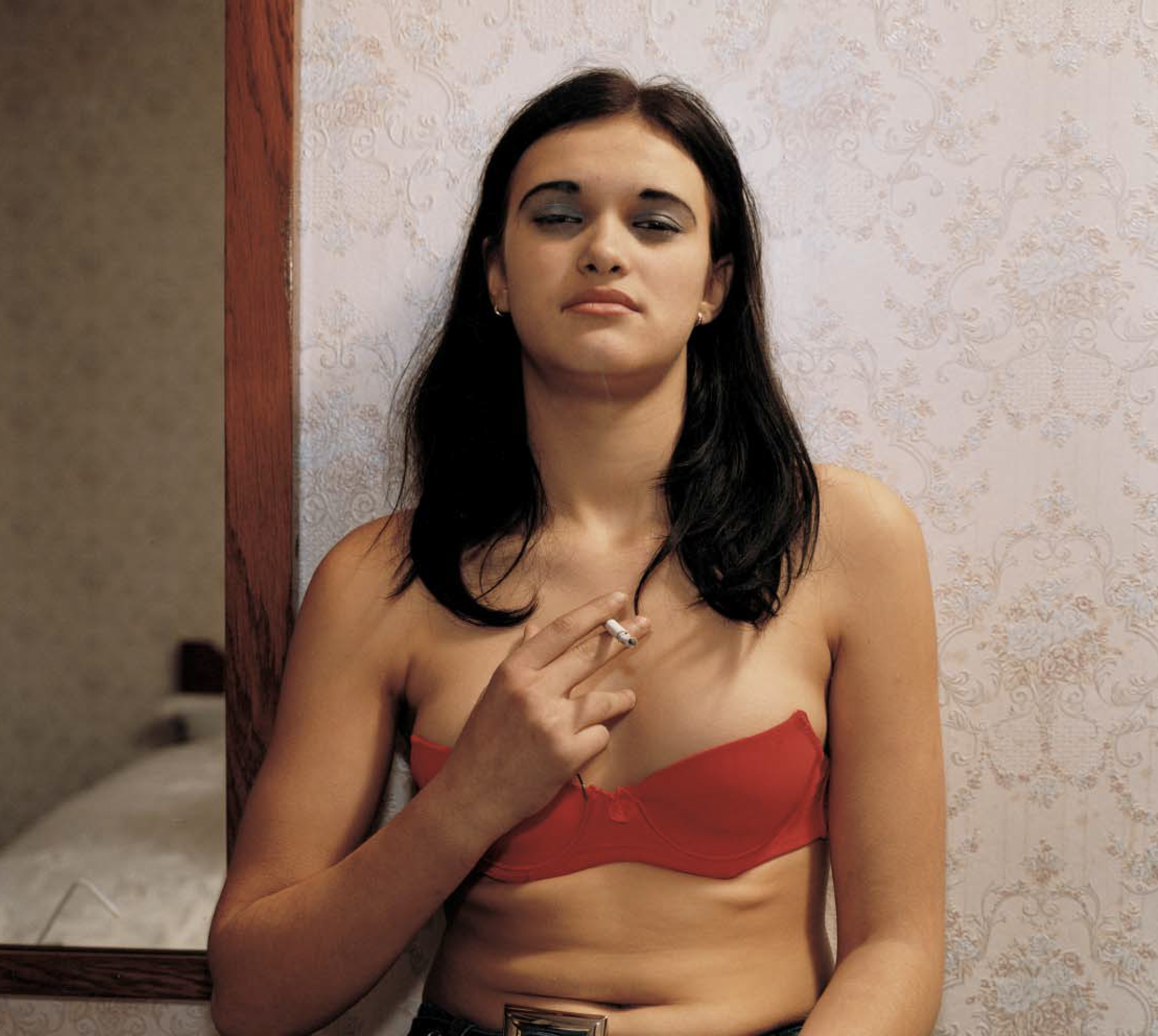

Photograph by Matthew Donaldson

No wife? No problem. More and more single men are paying surrogates to bear their children.

TO SAY HE WAS HURT WOULD BE AN UNDERSTATEMENT. JOE K. WAS DEMORALIZED. Here he was, the 39-year-old CFO of a big-time financial-services company in Boston, a major catch for any right-thinking woman, and he had just wasted 18 months of his life on a girlfriend who got cold feet. The two of them had

talked about moving in together. They had talked commitment. Joe was ready

for the whole till-death-do-us-part-and-two-kids-in-the-yard thing. Then one

day she tells him she’s just not into it.

So like any guy with a desire and a modem, Joe went fishing on the Internet.

He knew what he wanted: someone reasonably attractive. Intelligent. Personable.

And, of course, with no genetic complications, like a history of cancer in

the family or some uncle who lost a foot to diabetes. There were hundreds

of candidates out there, college girls, mostly—caught in meadow poses or

sitting at their desks—and all willing to give Joe exactly what he needed: a few

healthy eggs so he could make his own baby.

“It was a point of desperation,” says Joe, who asked that his last name not

be used. “I wasn’t ready to dive back in and invest the time and energy it took

to build a relationship. But I didn’t want to risk not ever becoming a dad.”

Over the past few years, a tiny handful of guys like Joe—probably 100

or so each year—have been taking a page from the feminist handbook.

Facing down 40 with no partner in sight, they’re becoming single parents,

thanks to the magic of artificial reproductive technology and the burgeoning

surrogacy-agency business. They are buying eggs (up to $50,000 a batch

at the high end, depending on the donor’s looks, education, and professional

achievement); paying for in vitro fertilization using their own sperm

(as much as $15,000); hiring a young woman who will allow the embryo

to be implanted in her uterus ($30,000); and waiting nine months for the

joyous hand-off.

The cost for a surrogate birth—from medical and legal fees to hiring an

agency that will orchestrate it all—can run as high as $150,000. And, of course,

this brave new world of eggs for sale and wombs for rent comes with all sorts

of legal hassles and ethical problems. Paid surrogacy is outlawed in some

states, restricted to straight couples in others, and completely unregulated

in the rest. Critics also charge that cherry-picking such features as eye color

and height amounts to eugenics. (Not to mention the question of whether

attaching a dollar value to physical attributes implies that some people’s eyes,

for instance, are worth more than others’.) They also warn that surrogates

may be exploited.

“It’s terrific that men are challenging gender roles that say only women can

mother,” says Mary L. Shanley, a political-science professor at Vassar College

and author of Making Babies, Making Families, a study of reproductive technology,

surrogacy, and adoption. “But there are real ethical issues, no matter who

is involved, around the commodification of reproductive labor.”

Joe K., a six-figure-salary man, admits to feeling awkward when he visited a

prospective surrogate and her husband in North Carolina in 2002. The woman

was “a very young 21 years old,” as Joe puts it. (The typical surrogate is in her

late 20s.) She had little education and clearly needed money. But after months of genetic- and disease-screening tests, she suddenly backed out, saying she

couldn’t bring herself to do it. Joe was devastated that the agency had let

someone who was clearly unstable get so far into the process.

But her decision allowed Joe to meet a second surrogate, a married mother

of two from Missouri. Joe’s first phone call with her lasted hours. They discovered

they shared a birthday. The woman said she had always felt an urge

to help someone in this way and that she wanted to offer her eggs and her

womb. In December 2003 she gave birth to Joe’s son.

For three days after the delivery, Joe stayed in a hospital room down the

hall from hers, feeding and caring for the baby. “Everybody at the birth was

crying,” Joe says. “This woman and her husband had made this commitment

and it’s a special time for them as well.” The surrogate, who was paid a $20,000

fee, would stop by his room daily. She’d play with the newborn’s fingers and

say, “He looks just like you, Joe.”

THE UNITED STATES IS ONE OF THE FEW COUNTRIES IN WHICH PAID SURROGACY IS LEGAL, thanks not to federal laws but to decisions in a number of state courts. Yet even here prospective fathers can find themselves on shaky ground. Some states say surrogacy contracts are unenforceable. Others recognize them but say no money can change hands. And in some cases, surrogate mothers

who also provided the egg have won custody of the child. This patchwork of

conflicting laws forces some would-be dads to cross state lines so they can

become fathers in a friendly jurisdiction.

That’s how Mike Carper, the international general counsel for a telecom

company in Washington, D.C., finds himself speeding along the Potomac

River toward Virginia on a bright spring morning. He is headed to a clinic

where the woman he has hired as a surrogate is having her monthly sonogram.

Carper, with his Anderson Cooper good looks, seems an unlikely

candidate for fatherhood. He is a world traveler. He wears Diesel jeans, British-

rocker boots from Calvin Klein, and a pair of Italian Persol sunglasses

he bought in Rome last week. (“Those damn Italians,” he says. “They keep

making things I have to buy.”) He also drives a Porsche convertible, and so

there is one aspect of parenthood he dreads: “driving a big, honking SUV.”

Carper recently gave up his sprawling bachelor pad in D.C., where surrogacy—

paid or not—is illegal, and moved to a house in nearby Maryland,

where it’s allowed. His surrogate is a married woman named Carey who

lives in Virginia. Since Virginia forbids surrogacy to single dads, their contract

requires Carey to travel to Maryland when she delivers Carper’s twin

daughters on August 4. (They have scheduled an appointment for induced

labor.) He has already petitioned the court to have only his name placed

on the birth certificate—a fairly standard practice that will help establish

Carper’s custody and absolve Carey from parental responsibility if, for

example, Carper dies.

Like every man I spoke to who has used a surrogate, Carper has always

known he wanted children (“Probably since my teens,” he says). But he’d

spent his life chasing a career, not fatherhood. By the time he hit 37, Carper decided to get serious about making babies. His first four attempts failed.

He had bought eggs from three donors at around $7,500 a batch and had

them fertilized and implanted in two separate surrogates at $25,000 for each

attempt. The embryos didn’t survive. Friends suggested he either consider

adoption or give up.

“When I didn’t get pregnant, I was like, ‘Shit, what’s wrong with me?’”

Carper says over the reggae mix pulsing from his stereo as we speed down the

parkway past Georgetown University. “Not to mention the fact that you just

spent a shitload of money on this. And ultimately you start saying, ‘Maybe

this is not meant to be, maybe this is not right. Maybe this is a sign from the

universe that I should get on with my life.’ But it became a project, a quest.”

Everything finally fell into place last fall, when Carper’s surrogacy agency

handed him a profile of a woman we’ll call Julie, a prospective egg donor.

She was a “friendly and talkative” 32-year-old married mom, the report

noted, with “positive energy,” auburn hair, and “huge green eyes that sparkle

with good humor.” She was slender and appeared “to take good care of

herself.” The packet included a photo of her with her husband and children,

and another of her as a young girl. Carper met her, liked her, and agreed to

buy her eggs.

“I understand how people get hung up on the whole weird Nazi engineering

of all this,” Carper says. “But it’s not much different than the way anyone

chooses a mate. At some level everybody’s looking to upgrade the gene

pool. This process just forces you to think about it in a fast-food scenario.

All you really want is your burger, and you want it now, and you want it

your way.”

Like any expectant dad, Carper is eager to share the details surrounding

the mystery of creation. He explains how hormones are injected into the

egg donor to “kick up the volume for harvesting.” He tosses out terms like

intracytoplasmic injection, in which his sperm is frozen, its tail later broken

off, and the head inserted into the egg. He explains how drugs are used “to

thicken the lining of the surrogate’s uterus,” so the foreign embryo will find

a welcoming environment. And like any proud papa, he carries pictures of

his kids, stacks of sonograms in a manila folder. “These are actually great

embryos,” he says, pointing out the smallest of dots, captured in the streetlamp

glow of the sonogram, somewhere in a sea of black and staticky silver.

He has plenty more that show the twins’ evolution to tadpoles and then

sea monkeys.

Carper, who has two graduate degrees in law, is as obsessed with the mechanics

of all this as he is with the idea of being a dad—particularly with the fine points of nursing. “I told this woman the other night that you can get artificial breasts and breast-feed that way,” Carper says with amusement. “And she’s like, ‘That is too twisted. You cannot even go there.’”

MATERNAL FETAL ASSOCIATES OF THE MID-ATLANTIC IS HOUSED IN A LOW BRICK BUILDING set amid green fields, strip malls, and the bulldozed earth of new condo developments in suburban Virginia. Carey is in the exam room when we arrive. She is marooned on her back, shirt thrust up to her bra, exposing an expanse of belly lubed with gel. The room is dark and cramped. The afternoon light

frames the window shade.

After greeting Carey, Carper asks the nurse, “What are you measuring now?”

On a cluttered table sits a monitor, where Carey’s sonogram is playing.

“Brains,” says the nurse. “Plenty of gray matter.”

“Good,” says Carey, reaching over to pat Carper on the leg. “They’re gonna

need that to support you someday in the manner to which you’re accustomed.”

Carper laughs. “Can we take some picture captures?” he says.

No, says the nurse; the twins are so big now they won’t fit on the monitor.

Carey is attractive and friendly, with blue eyes and a broad smile. She and

Carper have been friends since they worked together, 10 years ago. When

Carper asked her to be his surrogate, she agreed, with her husband’s consent.

(“He’s probably the person I’m most grateful to,” Carper says. “This guy has to

go to work and explain to his buddies why his wife is pregnant with another

man’s babies. I send the guy Omaha steaks whenever I get the chance.”)

Carey agreed to help Carper after her attempt to have a second child failed.

Rather than go the in vitro route, she and her husband adopted a son from

Russia. She surprises me when she says that she’s opposed to assisted reproductive

technology. “That for me is like theft,” she says. “There are over a million children in Russia alone who do not have moms, and if I can make a difference to one child, that’s worth it.” But then why help Carper? “It’s a personal decision, how you have kids,” she says.

At lunch, in a bustling, nautical-themed restaurant, Carey is open about

the role she’s playing and the criticism she faces. “Basically, there are people

who feel like, ‘You’re selling children,’” she says. She doesn’t see it that way,

since she and Carper are good friends, though she is being paid $25,000,

which she’ll use to fund her children’s education. After the birth, he also

plans to send her and her husband on a vacation to St. John, where Carper

owns property. “The other question I get is ‘Is he gay?’”

In fact, he is. And though he has a partner, his plan all along—since this

is his quest—has been to raise the girls on his own. Interestingly, part of his

contract with Carey requires that if either he or she has emotional issues after

the birth, they will attend therapy together, paid for by Carper. He wants his

daughters to know Carey and know that she carried them, but he does not

want them to know Julie, their biological mother. (Julie is, however, required

by contract to notify the surrogacy agency of her whereabouts for 18 years in

case of medical complications—for instance, if one of the girls needs a kidney

transplant.) That’s why Carper didn’t ask Julie her last name: So he couldn’t

give it to the girls if they asked for it.

“I never want to lie to the kids,” Carper says. “Because at some point they’re

going to come to me and say ‘I want to meet my mom.’ And you know, like, ‘Fuck

you, man. I want to go live with a normal family. I bet my mom is great!’ And

I want to be able to say, ‘You know what? I don’t know who your mom is. All I

know is that she has her own family, and I promised her before you were born that I would provide a good home for you. And you know what? You’re living it.

Now get your ass upstairs and clean your room and get on with your life.’”

ARTIFICIAL REPRODUCTIVE TECHNOLOGY IS A $3 BILLION–A–YEAR INDUSTRY IN THE United States. It is also largely unregulated. No state or federal agencies

directly govern its activity. (The American Society of Reproductive Medicine

encourages surrogacy agencies to follow certain guidelines, including a suggested

cap of $10,000 on payments to egg donors.) As such, the practice is

susceptible to abuses, critics say. There are people who want a child so badly

they’ll mortgage their home to get one. The more desperate they get, the

more lucrative the business becomes for the doctors, labs, surrogacy agencies,

donors, and surrogates, all of whom make money with each new attempt

to get pregnant.

Debora Spar, a professor of business administration at Harvard Business

School, argues that our culture shies away from the economic realities of

surrogacy: that cells are being bought and sold and that surrogates are not

“humanistic angels from above” but are actually paid workers. “For some

reason, when we talk about babies, we don’t seem willing to consider that

this is a business, that there are commercial aspects of reproduction that

are just exploding right now,” says Spar, whose recent book The Baby Business

makes a strong case for the types of guidelines that regulate adoption in the

United States. “We need to fess up to what’s going on, to move away from the

emotion-laden language and get some transparency, so everyone can make

better decisions.”

Beyond the business aspects, Spar is also concerned with access to surrogacy

and whether insurance policies should cover it. “This is a wealthy man’s

market. If you’re a single guy who wants to do this, you darn well better be

rich. So really, the harder question that is not being raised is: Are we okay with

surrogacy being a luxury good?”

Because of the availability of paid surrogacy here, the United States has

become a shopping destination for single men and infertile couples from

around the world. In Norway, it is illegal for a lesbian couple to be artificially

inseminated. In Germany, it is nearly impossible to enforce surrogacy

contracts in court. Italy bans the use of donor eggs and sperm, and severely

limits artificial insemination. And while both the U.K. and Australia allow

surrogacy, they forbid payment for it.

Dale Stevenson, a 30-year-old high-school teacher from New South Wales,

Australia, is expecting a child with a San Diego surrogate next year. He seems

young to have given up on finding a wife. But Stevenson, who has the support

of his family, and the $95,000 to pay for the process thanks to his former job

as a stockbroker, has what he considers a perfectly fine reason. “I just found

I’m one of those people who doesn’t need a mate,” he says. “I find it harder. I

prefer to live on my own.”

The irony is that children dramatically change one’s life. But surprisingly,

Stevenson’s sentiment was repeated by several other single men. And it

makes you wonder: While it seems fine and admirable that single men are choosing the responsibilities of fatherhood, are they simply giving up on finding a partner? Joe K., the Boston financier, has a mother and sister helping him with his 2 1/2-year-old son, acting as maternal figures. And though his life is filled with the chores of parenthood—and though he does date—he has no immediate urge to have a mate at home. “It’s not a priority,” Joe says.

Same goes for Mike, a 35-year-old manager at a Colorado high-tech company.

Mike seems to have worked it all out. He says he’s had only two girlfriends

in his life, relationships that lasted about four months each. Yet he

was certain, almost as soon as he left his 20s, that he would have children

and he would have them alone. “I just never met the right person,” he says.

“I guess I never opened myself up for the possibility either. Like, I’m not real

outgoing. And I was always uncomfortable meeting women. You know, my

two cents of psychoanalysis, I would say it was always a fear of rejection.”

But he still hoped to have children. “I wanted to share my life,” Mike says.

“It wasn’t like a biological clock ticking. I like kids. I like doing activities, even

if it’s a girl dressing up, or a boy throwing the ball. I like it particularly when

young kids—I don’t want to say ‘unconditional love’—but the way they look

up to you, and run up and put their arms around you.”

Mike, a cherubic-faced guy with shocking blue eyes and a razor-sharp part

in his hair, who has decorated his living room in African statuettes and Van

Gogh oil reproductions that he bought online, has given up a lot to have kids.

A former skier and scuba diver, he has put all that on hold. And it’s clear that

he’s a very loving and tender parent.

As he flips through one of his daughter’s baby books, holding his little girl

in his lap while her sister sleeps on a quilt by a fireplace of ceramic logs, he

stops on a page devoted to their two mothers. There he has pasted pictures

of a blue-eyed blonde (the egg donor) lying on a living-room floor and a very

tired-looking woman (the surrogate) holding the newborns in the hospital.

“That’s your surrogate,” he coos to the baby. “And that’s your mommy there.

She’s pretty, just like you.”

The girls, in fact, strongly resemble Mike, and he explains that that’s because

he chose a donor with a similarly fair, northern-European complexion.

“I wanted someone who looked like me,” says Mike, who grew up an only

child. Sometimes, when he’s at Costco with the girls, strangers will stop and

fuss over the babies, asking the girls in a well-meaning singsong: “Where’s

Mommy today? Is she home and Daddy is taking care of you?”

“There’s this automatic assumption that I can’t be the primary parent,”

he says. He usually dodges the question, even with coworkers who wonder

where the girls suddenly came from. “I tell them it’s a long story, and I’d

rather not go into it. They probably draw the conclusion that I knocked

someone up.”

As for the girls, when they get old enough to ask about their mom, Mike

says he will have an answer ready. “It’ll be like, ‘There was this woman who

carried you . . . ’” he says, his voice trailing off. “Anyway, I’ll have it figured out.

I’ll tell them all families are different, that I really wanted kids. And that I love

them more than anything.”