Slave Drivers

DETAILS MAGAZINE

FEBRUARY 2003

Photo by Sasha Bezzubov

Every year, thousands of young women from Eastern Europe disappear into the violent underground world of sexual serfdom. And a few young pimps get rich.

ION VINATORU, A BUCHAREST PIMP WHO WILL RENT YOU A ROMANIAN SCHOOLGIRL ($65 an hour) or sell you a teenage Moldovan sex slave ($800 and she’s yours for life), is in a black mood.His plump frame is crammed into the passenger seat of a musty Renault taxi. His Prada-knockoff jacket and the blue power shirt he never changes—he airs it out overnight on a chair and has his wife iron it every morning—are getting wrinkled. He sighs like a man losing money. Then he jerks around and points at me with his silver Nokia.

“Look, this girls I show to you, they don’t speak too much good English,” says Vinatoru, 23, who goes by the name Nicu, which is embossed on the white cards he offers lonely businessmen on the city’s dark streets. “But they fuck good. If you like this ones,you take it. She go to you.” Nicu pins me with a boxer’s stare, his hooded eyes dead, until a grin crawls across his baby-fat cheeks and he snorts. I take a drag from my hand-rolled cigarette and try to laugh before looking out the filthy rear window,wondering what I’ve gotten myself into.

I’ve come to Bucharest to investigate the international sex-slave trade, a reported $7 billion–to–$12 billion industry in human trafficking that traps 700,000 women each year. Eastern Europe, in particular, has become both a hunting ground and an auction house for flesh peddlers. Impoverished girls, some as young as 13, are appraised like cattle, their bodies inspected by foreign buyers, breasts squeezed, asses slapped, lips mauled. Their innocence is taken by brutish entrepreneurs like Nicu who make a habit of sampling the product before selling it off to soulless strip-club managers and brothel owners in Italy, Greece, Japan, Germany, Israel, Turkey, China, Macedonia, Kosovo, and, of course, the United States.

For twenty minutes we’ve been sitting in this smoky cab outside a neon-lit grocery in Socului, a working-class section of Bucharest. The looted carcasses of Russian Ladaslie three deep on the sidewalk;Soviet-gray apartment blocks tower like asylums amid sickly trees on this foggy winter night.And here I am—as dusty trolleys full of shivering faces rattlepast—waiting to buy a woman.

I met Nicu outside my hotel three days ago. He stepped out of the shadows and offered me a teenager who gives blow jobs without a condom. “Clean,” he assured me, standing a block from where pro-democracy students faced down government tanks in 1989, and where Nicu himself had fought a knife battle—for control of the local walk-by market. I told him I wanted to buy a girl to work in a U.S. strip club for me,have sex with as many men as I tell her, and give me the money. Make me a rich man, just like Nicu. Nicu narrowed his eyes. “This is no problem,” he said. Nicu could even provide my purchase with an illegal U.S. visa—from a friend inside the U.S.embassy.

Knowing that the only possible way to infiltrate a trafficker’s trade would be with a slight degree of . . . dissembling, I’ve told Nicu only that I’m a magazine writer on a travel assignment in Romania (the strip club I’m recruiting for belongs to “a friend”). Nicu either has no curiosity or no imagination—or maybe he’s simply too greedy and blasé to delve any further. As I sit in this cramped taxi next to my photographer, Sasha, I’m worried about several things: That I may be breaking a law or two. That I may be crossing several ethical boundaries. That Nicu, who’s fond of clasping my elbow whenever he sees me and patting my lower back—the way you would pat someone when, say, you’re looking for a knife—would be disappointed if he knew what I was up to and might turn violent.

Nicu checks the time on his Nokia, the face of which displays a digital rose, a heart, and the word LOVE. One of the prostitutes arrives, climbing out of another taxi. She’s wearing a long brown overcoat with a fur collar. She is 22, slender, with a delicate face and hair dyed the color of rusted steel wool. She tosses a cigarette to the ground and wedges herself into the back seat next to Sasha.

Nicu cranes his neck and says, “She good, huh?” The woman, unsmiling, looks straight through me. We drive along muddy alleys patrolled by a few of the city’s notoriously vicious wild dogs until we reach a building with a glassed-in lobby. We climb the concrete stairs in silence and turn down a damp hall.Nicu, glancing over his shoulder, steps aside. The taxi driver, a fellow pimp named Cristi who looks like a cracked-out Ricky Martin in a red Champs pullover, opens the door toa barren room. A bored-looking girl smoking a butt at a low wood table rises.

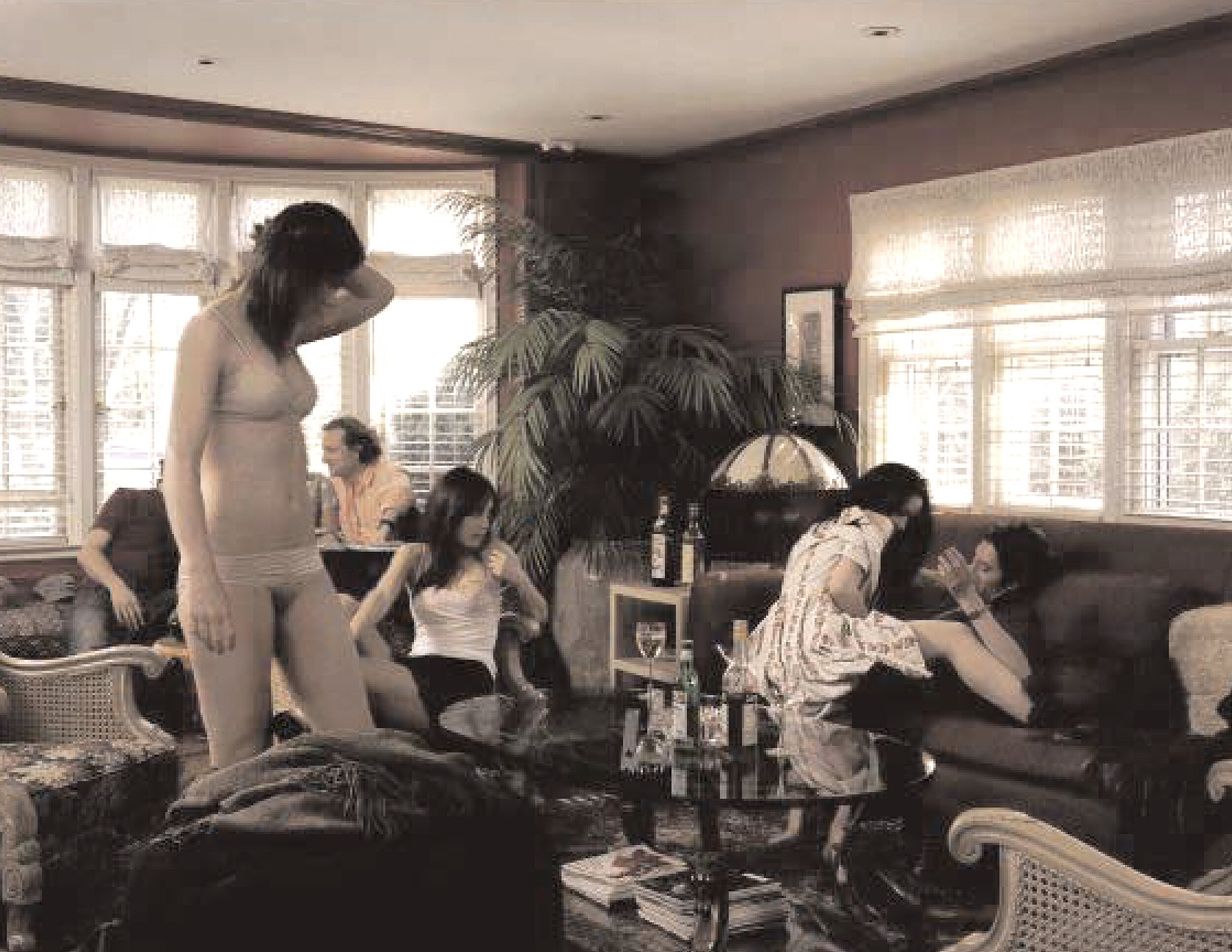

The redhead, whose name is Mari, joins the bored girl, Alexandra, a toothy strawberry blonde. Without our asking, they begin to strip. Nicu smiles, showing sharp infant teeth. He looks like a hungry Bat Boy.

“So, what you think?” he says. “You take?”

The room is silent. I’m suddenly aware of the toothpick Nicu is chewing. It’s an awful moment. He’s asking me to assess these women, to critique them as they undress. And though I am supposed to be someone who’s at ease with buying another person, I’m afraid to hurt their feelings.

“You’re very pretty,” I lie to them transparently. “Both of you.”

“Go ahead,” Nicu says, “you feel this.”

Alexandra has shed her tight jeans and her halter top; she’s standing barefoot in a pair of black panties. She is a big girl with large breasts and a small appendix scar. Mari,who’s finished peeling off her pants, is standing in her bra and underwear, tugging self-consciously at her shoulder straps. She is nursing a 2-year-old daughter, Alexandra explains, and does not want to expose her breasts.

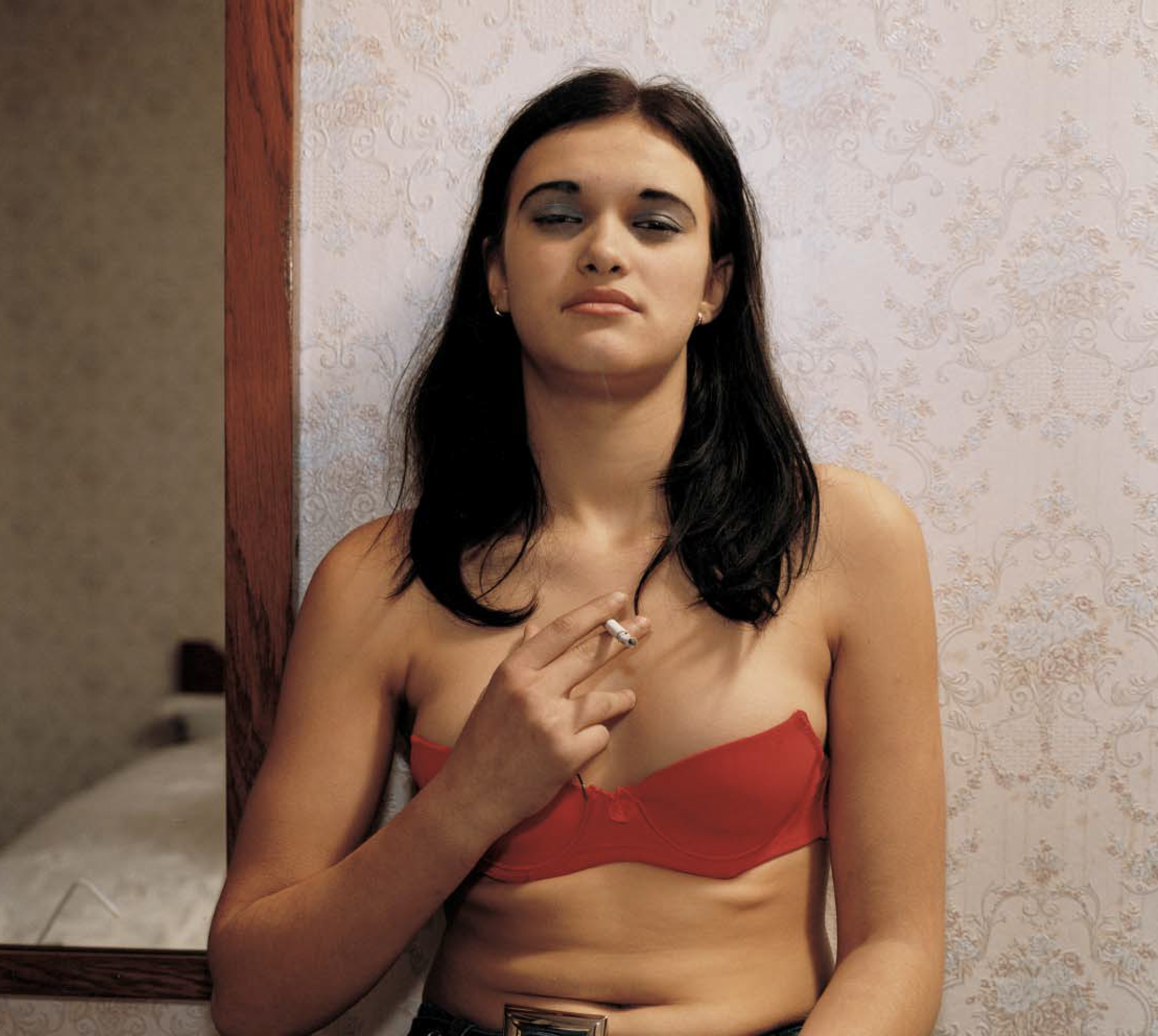

Nicu growls something at her and Mari bows her head, gently shaking it. “It’s okay,” I say, but Nicu is insistent. So I walk up to the girl, shielding her from the others as she lifts her satiny red bra. She looks up at me, beneath thick blue eye shadow, drilling my face—as though this were all my fault.

HUMAN TRAFFICKING IS THE FASTEST-GROWING FORM OF ORGANIZED CRIME IN Eastern Europe. In the Balkans, where it is concentrated, the trade has become more lucrative than heroin smuggling; widespread corruption among local police and a lack of uniform laws make it a relatively low-risk, high-profit endeavor. Worldwide, such trafficking has an insatiable market, thanks to Webbased porn (you’re always just a click away from Ukrainian girls going at it in a Kiev apartment) and the multi-billion-dollar sex-tourism industry.

As a result, traffickers move roughly 200,000 women—most of them from the former Soviet Union, especially Ukraine and Moldova—through Eastern Europe each year. (The CIA says the Russian mafiya brings some 4,000 to the United States.) These women—poor, ill-educated, raised in decrepit towns like

Mari’s birthplace in the Carpathian Mountains—lack job options. In Romania, 7 million citizens,a full 30 percent of the population, live below the poverty line; the average weekly salary is about $28. Despite the bloody 1989 overthrow of Communist strongman Nicolae Ceausescu, the country remains—even after

two years of middling growth—an economic backwater. Drawn to a notional Western utopia of venti lattes and Versace, some women find themselves involved with double-crossing traffickers and, before they know it, enslaved.

“These are girls from normal families who see there is no hope for them or the people around them,” says Dani Kozak, a victim-liaison officer with the International Office of Migration, an agency that works with the United Nations to counter trafficking.Kozak’s Bucharest office has repatriated 600 victims over the past two years. “Many have heard the horror stories,” he says,“but think it won’t happen to them.”

The biggest trafficking networks are ruled by brutal Russian and Albanian gangs, which provide security, travel support, contacts with brothel owners, and forged documents. But there is plenty of trade to go around, especially for industrious freelancers like Nicu.

In many cases, the trap is set like this: A recruiter working on commissions as low as $20 (usually a well dressed woman in her thirties) approaches a young lady, typically a teenager, in a bar, café, or disco. She spins a Cinderella tale of riches—$1,000-a-month jobs in Milan or Paris, as a waitress, nanny, housekeeper, dancer. The reality is more modern-day Grimm’s fairy tale. The recruiter either smuggles the victim out or hands her to someone else, who then pays off border guards, spirits her to a hub town like Bucharest, and sells her to a pimp or another trafficker who will ultimately sell the girl for a higher price. (If she is tall and beautiful, she can fetch $800; a virgin may go for as much as $2,000.) The pimp seizes her passport, tosses her into a bleak apartment with other women, and announces that she is his property. The pimp then informs the woman she must work off the money he paid for her—typically an inflated figure that can reach $5,000.

Ana, 19, a beautiful blue-eyed Moldovan—the one Nicu sent to my hotel room that first night, the one available for unprotected oral sex (I didn’t accept)— offered her sad tale as she helped herself to Red Bull vodkas and Toblerones from my minibar: She was sold by a family friend to a Bucharest madam for $700. Her country, sandwiched between Romania and Ukraine, is renowned for its beautiful women. By some estimates, nearly 80 percent of the women trafficked in the Balkans are Moldovan. You can actually visit villages in Moldova that are absolutely devoid of women under 23. Those who remain sometimes stand on muddy roadsides alongside cornfields selling sex to truckers for as little as $5. Ana tells me she believed she would be an exotic dancer but instead found herself forced into sex with up to six men a night. After a month of servicing Turkish, Japanese, Italian, and American businessmen—and reimbursing her madam for rent and food—she was no closer to paying off her debt.

“I don’t trust no one now,” says Ana, as she leans forward in her chair, shaking an empty glass at me. “I hate this life. My mother, she kill me if she knew what happens. I have to go fuck 80-year-old man who fucks me and says, ‘Do you like it? Do you like it? Of course you do, you bitch. Of course you like it.’ And I have to just take it and smile and say, ‘Yes, I like it.’”

The training Ana is receiving in Bucharest will increase her resale value when she’s sent west. She might work a few months in her next home, then be sold again. This is known as the carousel—a life of perpetual servitude. Some women are kept under lockdown in the backs of bars or brothels; others, like Ana, are allowed to see clients by night but kept inside all day. Usually they’re threatened with beatings or murder if they go to the police; sometimes they’re told they’ll be arrested for prostitution or for entering the country illegally. And these women have good reason to fear the police,many of whom, especially in Kosovo and Macedonia, are in league with the pimps.

“The women begin to see themselves as criminals,” says psychologist Catalin Luca, executive director of a victims’-assistance program in Iasi, a Romanian city and trafficking bazaar that borders Moldova. “Also, they are ashamed of what’s been done. Many would be viewed as worthless by their families.”

Ana told me that she hoped to return to Moldova for the holidays to see her family. “I don’t tell no one what happens,” Ana says to me, her eyes growing wide. “I just want to see my mother. I hate all these people here. Marina”—her madam—“Nicu, everyone.”

IN THE BUCHAREST SEX TRADE, NICU IS WHAT’S KNOWN AS A COMBINATION BOY. One of countless whispering hawkers, he matches the specific desires of businessmen (tall, blonde, green-eyed) with women owned by the pimps and madams who run the city’s myriad escort services.

Nicu is by no means a big fish. He’s more like a guppy. But in this toxic free for-all trade, guppies can mutate into sharks. And that’s what worries the Bucharest police. I am catching Nicu at a crucial point in his career. After five years as a combination boy, he makes a fine living. He also runs what he calls a modest $30,000-a-year sideline moving human product to Milan, Munich, Haifa, and Amsterdam.

Most of the women Nicu wants to sell me work for other pimps. Nicu doesn’t want to own girls. “It’s too much trouble, too much money,” he tells me. We’ve met at a nautical-themed bar a few blocks from the Inter, as the girls call the hotel, the walls thick with drooping fishnet and cork.

Nicu is sipping apple juice. He says he’s been sober for three months. He hasn’t even smoked a cigarette since he blew $35,000 on roulette at the Princess Casino and had to sell his BMW. He’s wearing his blue power shirt again. His cell phone is ringing. His black hair is perfect.

“I tell to you,” Nicu says, as he pockets the phone, “we must trust each other.” He dead-eyes me as his sausaged right forefinger (the result of a knife fight) tickles his glass. “Understand?”

I’m here to give Nicu $800 for a woman. Her pimp will get that money. Nicu will pocket an additional $500 from me for brokering the deal. Then, Nicu says, he could arrange, for additional money, an illegal U.S. visa from a friend at the U.S.embassy. The friend, says Nicu, will forge a series of documents and have a stamped, three-month visitor’s visa pasted into the woman’s passport. Like many trafficking victims, the woman will simply overstay her visit and become an illegal alien.

Nicu is in a good mood tonight.He says he’s just come back from having sex with Ana. He “fucks good” all the women, he tells me, one of the perks of his job, usually offering them $20 for the pleasure. His wife, who knows what he does for a living, doesn’t know about this, he says. She’s too busy playing cards with friends in their two-room apartment (while Nicu paces the hotel sidewalk from 9 P.M. to 5 A.M.) and looking after their 5-year-old daughter (whom he’d like to send to university someday).

Nicu found his way into the flesh trade when his first career failed. He started out as an amateur boxer. He won his first fight, then lost the next four. When he was 13, he says, his father succeeded in drinking himself to death. Five years later, Nicu’s friend, a taxi driver named Gabriel who’s stationed near the Inter— and who is also a combination boy—brought him into the business. Prostitution is illegal in Romania but is tolerated on the streets (you can pick up a gypsy near the university for $20); it is amazingly institutionalized at several of the city’s top hotels,where concierges, bellboys, and barmen have been known to offer, unsolicited, the best-heeled hookers for $130. At the Inter, one of the priciest hotels (nightly rate: $180), I was bombarded daily—at the door, the desk, the elevator—with the same question: “You need companionship tonight?” (A security manager for the hotel’s parent company later told me the chain was unaware of any criminal activity but was “very concerned” about my experience, and intended to launch an immediate inquiry of the Bucharest staff.)

Romanian traffickers tend to be gypsies (one Bucharest cabbie called them “niggers, like you have in the Bronx”). Just as often, traffickers are former members of the intelligence community, running so-called security services. Adina Cruceru, a detective with the Interior Ministry’s organized-crime squad, says trafficking networks are difficult to break because there is no single gang but rather many small gangs, most of which are also involved in drugs, gun trafficking, and money laundering. “We can use undercover officers to catch them, but it takes a lot of time to infiltrate and we don’t have the resources,” she tells me, admitting,“Corruption is a problem too.”

In order to run his business, Nicu says, he pays off a number of people. If he provides a prostitute for $130, he gets about $60. Of that, he gives $10 to the doorman and another $10 to a patrol officer. “Everybody make the money,” Nicu tells me. When he sells a woman in a place like Milan, however, he gets a $600 commission and a monthly kickback from her earnings. “It’s better business, the selling,” he says, shrugging. “I do more if I can.”

THE WOMAN SITTING NEXT TO ME IN A NOISY COFFEE SHOP HAS NO IDEA SHE’S being sold. Across from her are Nicu and another man named Aurel, a former bodyguard who runs “a talent agency” sending girls to exotic-dance clubs in Kosovo and beyond. (Cruceru told me that these agencies can be slave-trading fronts and that a number of them have recently been raided.) Aurel mentions that he can help me get pictures of children performing sex acts. I’m not surprised: Ceausescu outlawed birth control and abortion, and the country remains flooded with orphans, who are often employed in pornography.

Ramona is the last of a dozen women Nicu has offered me over the past week. She’s 21, in her second year as a university finance student, and has recently applied for a secretarial job at the U.S. embassy. She is wearing a beige sweater and matching pants. She has been told only that I have a job for her in New York.

Ramona is different from the other women I've spoken to: She’s educated, but no less desperate for a shot at the American dream. I ask her, as I’ve asked all the girls, whether she’s willing to dance nude.

“I don’t, but I will,” she says candidly. “My body is not so good for dancing.” Ramona has the large dark eyes of a child. As we speak, I realize that she’s known Aurel for only a few weeks; she’s just met Nicu. Unlike the other women presented to me, Ramona is a fresh recruit, and this knowledge unnerves me.

Despite her intelligence, in her desperation, she is about to walk through a door she’ll never be able to shut.

“Will you have sex?” I ask her.

“No,” she says, taken aback. “Unless I like someone. It is my own business.”

Nicu and I leave Ramona to her coffee and go outside. Feigning anger, I ask Nicu what’s going on Ramona says that she’s not a prostitute. He pulls me over to a man who’s wearing Lakers sweatpants tucked into black military boots. Nicu repeats what Ramona said. The man throws his head back and sneers. He and Nicu both laugh. “Look, she will do what you say,” Nicu says to calm me. “Otherwise . . .” He karate-chops the air. This time, no one laughs.

Later, Nicu gives me a tutorial on how to discipline a prostitute. He says that I should keep her passport, take half the money every time she sees a client, make her work seven nights a week. What if she gets tired? I ask.

“She sleep in the day,” Nicu says with a shrug.

We are standing outside a strip joint called the Million Dollar Club. The façade is decorated with two twenty-foot cutouts of topless dancers. Nicu gets paid every time he brings someone here. Inside, they greet him like a king, which suits him. Earlier, Nicu quizzed me about the New York Mafia and told me his favorite movie is Casino. “Sharon Stone,” he said, shaking his hand like it was on fire. “De Niro!”

But right now, I have another question. What if the woman I buy runs away, say, with a client?

“You call the man and say, ‘Look, you want to be with this girl, is no problem,’” Nicu begins. “‘But she belong to me. She no belong to you. You must give me $10,000.’ The girl, she know this. She tell the man, ‘You must give the money.’ If the man say no, you say, ‘Let me talk to the girl.’”

Nicu has been touching my forearm as he speaks. Now he puts his finger around my elbow, and locks his eyes on mine. We are friends, co-conspirators. “And you say, ‘I send someone to get you in one hour,’” he continues. “When the girl, she come to you, you send her to another country. End of problem.”

Yeah, I say, but what if the man won’t let her go? Nicu looks disappointed in me.

“If this happen in my city,” he says, with what I believe is a dash of De Niro bravado,“ I kill the man.”

MORE THAN 100 CRIME-FIGHTERS FROM ACROSS EASTERN AND CENTRAL EUROPE are sipping red wine and eating yellow cubes of cheese in a one-room cement building behind the General Inspectorate of the Border Police. On this late November night, they are here for a weekend conference aimed at codifying anti-trafficking laws and procedures for handling victims.

Last fall,the transborder crime-fighting unit of the Southeast European Cooperative Initiative (SECI) launched a ten-day sweep of brothels and strip clubs in its eleven member nations. (It received logistical support and intelligence from the local FBI,as well as $140,000 from the U.S.government.) In more than 20,000 raids, the group arrested 293 traffickers and identified 237 trafficking victims.

“The main goal in Romania was to get the trafficked women back home,” says Colonel Gabriel Sotirescu, who directed the SECI task force, which is headquartered in Ceausescu’s former palace. “And we succeeded in getting hundreds out. We also succeeded in dismantling several criminal networks. But in order to be more efficient in the future,we need the cooperation of every country.”

One week later, George W. Bush is speaking to a rain-soaked crowd of 40,000 people in Bucharest’s Piata Revolutiei, welcoming them to NATO and patting their overburdened backs for opening their doors to free-market reform, as pickpockets work the crowd. A few blocks away, Nicu and I are huddled in the fishnet bar. I’ve decided to buy a woman named Carmen. For additional money, Nicu says, he could get me that visa and a friend in our embassy can forge documents.

Carmen is not an obvious choice. She’s not attractive, not the way the other girls are. Not over-the-top sexy or mouthy. She is, in fact, matronly. Carmen is 24. She is from the Moldavia farming region of Romania. Her family, she says, is so broke that she chose to prostitute herself in Bucharest in exchange for a $300 loan from Nicu that helped her father pay an electricity bill so he could restart his failing home-bakery business. She is just starting to learn what this “loan” really means. She arrived in Bucharest four days ago. When she came to my hotel room, Nicu told me not to “fuck her too hard, she new.” Again, I turned down the offer.

But Carmen struck me—as well as my photographer, Sasha—with her maturity, her pride, her sacrifice. “My mother knows I am in Bucharest to make some money, but she don’t know how,” Carmen tells me as she sits in my room sipping a Coke, the sprawl of the city’s Beaux Arts architecture and Soviet-issue apartments visible beyond the terrace doors. “We are three children, and I don’t want my mother to think I am not a good child.” I ask Carmen the same questions I asked the other women, and one more. Is it difficult, to do what she does, to work for someone like Nicu?

“I’m only in the beginning,” she says. “Maybe after a long time, then I start to like this business.” Her face is slack, until a grim smile emerges, “I don’t know.”

I’m staggered by her resignation—and by my own blithe toying with her life. I’m not sure how far I want to take this. Sasha and I have discussed these women earnestly and have begun to believe we can actually save someone. Here we are, with money and opportunity. Maybe we can bring her back to New York, have her stay in Sasha’s apartment for a month, help her get a waitressing job or something. But then what? What if someone threatens her family in Romania, or if she hates her stage-managed life in America even more? Who do we think we are?

“Do you know that girls who go to foreign countries for this work wind up in a lot of trouble,” I ask, “with bad men and no way to get out?”

“Yes,” she says, and shrugs. “It’s on TV and the newspapers. There are a lot of girls that go to Italia, and some men promise work in this place and that. I think that if I find this kind of man, I would like him to tell me what I will do there. If I agree, I go. If not, I don’t go. But I would like him to tell me first.”

Cruceru, the detective who’s interviewed countless trafficking victims, told me that among her biggest problems in educating women is that few believe such a fate will befall them. With that in mind, I ask Carmen if things are that bad for her here in Romania.

“It’s my dream to leave,” she says, staring at her cigarette. “Maybe it’s possible to make my future in another country, because here in Romania I don’t have a future. Because here,for example, I don’t want to stay in the countryside all my life. I want a home for me, and maybe other things. This is my dream.” Then she stands up and starts undressing.

NICU IS FREAKING OUT. IT’S MID-DECEMBER, TWO WEEKS AFTER MY RETURN TO America, and he’s on the phone, telling me the visa he offered for Carmen could take longer than he promised. He’s blaming the delay on Bush, claiming the president’s recent visit has seriously hindered his access to visas, that his friend on the inside is having trouble. I’m not surprised: I’ve just heard from the FBI’s legal attaché at the U.S.embassy in Bucharest, as well as the embassy’s general counsel, Jay Smith, that forgery has indeed been “a problem.” The embassy, says Smith, recently dismissed a Romanian clerk who they believed was handling forged documents—and selling visas.

“Look,” says Nicu, growing irritated, “you comes back!” If I’m in such a hurry, he says, I can simply take Carmen to the embassy myself, where, as an American, I could easily request a three-month visitor’s visa “for my girlfriend.”

While still in Romania, I’d concluded that bringing Carmen to America would be far too complicated. My final plan—even if Nicu came up with a forged visa, proving that this can indeed be done with minimal effort—was simply to call Carmen and tell her my friend’s club had closed. Nicu could keep my money, and no one would be hurt—not immediately, at least. Only it wasn’t turning out that way.

“Look, I tell to you,” Nicu says louder, over the satellite echo of his Nokia, “you must wait. It is no good right now.”

Forget it, I tell him. Forget the whole thing. I’m no longer interested. He’s shocked, of course. Silent, for a moment. “Okay, boss,” he says, adding that I can change my mind if I want. I hang up the phone, glad to be rid of him. But I know that in rooms all over Bucharest, Carmen—and Mari, Alexandra, Ana, and Ramona—have had their minds made up for them.